Writing letters and emails in English: correspondence for the editorial office

Article information

Abstract

One of the main responsibilities of the editorial office is to communicate effectively with authors through emails, formal letters, and most importantly through decision letters. Even when the content is informative and constructive and the editor has only good intentions, if the tone and level of formality are not managed properly, the image of the journal may be negatively affected, which may deter authors from submitting papers to the journal again. Despite their best efforts to treat authors respectfully, some editors may unintentionally cause offense if they lack the appropriate sociolinguistic knowledge required for effective English correspondence. In order to ease the burden of the editorial office, this tutorial aims to assist non-native English speaking editors by demonstrating the basic format and principles of writing formal letters and email, providing tips on how to select an acceptable level of formality, and offering strategies to avoid unintentional rudeness. Specific tips include framing issues positively, using indirect language, and using hedging. Through this tutorial, non-native English speaking editors are expected to develop sociolinguistic competence to write professionally and improve their efficiency in corresponding with authors.

Introduction

Preparing academic correspondence can be challenging for both students and professionals [1-3]. In particular, peer reviewers and editors of international journals may find themselves at a disadvantage when having to correspond in English if it is not their native language. Even though online resources and letter templates for correspondence are available [4,5], cultural interference can still hamper reviewers’ efforts at providing critical and constructive feedback or rejecting submissions in a socially appropriate way.

Editors should also be aware that rejection letters may impact not only the submitting authors’ self-image, but also the journal’s image in the eyes of the authors; however, these negative effects may be reduced when letters are framed positively [6,7], delivered in a timely fashion, and customized to the recipient [8,9]. Early research showed that formal (as opposed to informal) forms of address in rejection letters can promote higher self-concept among job applicants, and that praise, indirectness, and explication in letters of at least moderate length can lead applicants to view the rejection letter itself more favorably [10]. By utilizing the proper level of formality and being polite, editors can further reduce unintentional miscommunication. To assist non-native English speaking (NNES) editors in the task of corresponding effectively, we provide a tutorial on crafting professional, socially appropriate letters and emails in English.

Basic Format and Principles

Formal letters

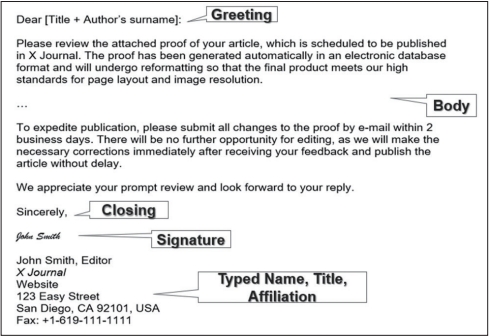

The block format of letter-writing, printed on letterhead paper, is the gold standard for business letters and is appropriate for a formal letter from a journal. Whether the message is sent by post or by email, formal correspondence in English should conform to the following guidelines.

Font: Use Arial, Helvetica, or Times New Roman, 12-point.

Heading: The journal name and address belong at the top. If not on letterhead, they should be typed single-spaced and preferably left-justified, although for design purposes they may also be centered or right-justified.

Date: Allow one line of space between the heading and the date, which may be left- or right-justified, or centered in the case of letterhead. The construction is: month day, year (e.g., December 25, 2021). However, other formats (such as day month year, or 25 December 2021) may sometimes be employed, especially by authors from Europe.

Inside address: Following four lines of space, the recipient’s name, title, and address come next, single-spaced and left-justified.

Salutation: Allow one line of space before the salutation. In a formal letter, the salutation should begin with “Dear” followed by the recipient’s title and family name, each of which is capitalized, followed by either a colon (:), which is formal, or a comma (,), which is considered less formal. Do not include the recipient’s given name on this line unless you are unable to distinguish the given name from the family name.

Body: Use block style, with one line of space between each of the body paragraphs. Do not indent paragraphs. Single-space all text, maintaining left-justification.

Closing: Allow one line of space following the last body paragraph, and left-justify the closing. “Sincerely,” is unequivocally the best choice of salutation for closing a business letter.

Signature and affiliation: After the closing salutation, allow four lines of space for the signature. The signature should be followed by the full name and title of the signatory, the affiliated institution, the institutional address, and the signatory’s email address, telephone, and fax number, including relevant country and area codes.

Emails

By their very nature, emails are regarded as less formal than printed letters. Nevertheless, they can be made to appear more formal by being formatted like a printed letter using the preceding guidelines (Appendix 1). Notably, the heading, date, and inside address may be omitted in email correspondence as this information is easily found in the recipient’s inbox. Furthermore, since email is already less formal than a printed letter, it may be acceptable in the first correspondence to address the recipient as “Dear” followed by first and last name without a title when the recipient’s title is unknown.

After an extended period of email correspondence with the same individual, formality tends to break down. At that time, a more personal touch may be introduced by utilizing first names in the greeting once one of the signatories has used only the first name in closing. Dropping the family name in the closing gives tacit permission for the other party to switch to a first-name basis if so desired.

Whether formal or informal, emails should include a subject line that informs the reader of the main topic in a direct way. When writing a subject line, use keywords, not sentences, and try to be specific. For example, “Revision due Friday” would make a better subject line than “Notice of an upcoming deadline.”

Level of Formality

Personal relationships between editors and authors, as well as one’s personal style and the culture of the journal, will influence the level of formality in editorial correspondence. When corresponding with an unknown recipient, it is most appropriate to use formal diction. After building a relationship with a submitting author, however, it is possible to relax the formality slightly if this is not discordant with the customs of the journal.

Opening salutations

As English modernizes and moves towards gender-neutralization, the opening salutation line has been undergoing changes. Where possible, it is still appropriate to begin a formal letter or email with “Dear” followed by a title and family name, but which title to use is presently in flux. Titles like “Professor” or “Dr.,” which are gender-neutral, can be combined with any family name as appropriate. Another advantage of the titles “Professor” and “Dr.” is that they are highly unlikely to cause offense in an academic context, where it can be assumed that most, if not all, recipients will have a doctoral degree. In contrast, “Mr.” and “Ms.,” while still in use by the majority population in the United States for general purposes as of this writing, may at some point be displaced by the gender-neutral “Mx.” If a recipient’s preferred form of address is unknown, the correspondent may choose “Mr.,” “Ms.,” or “Mx.” (or “Dr.” in an academic context) followed by the family name. Note that using someone’s first name only remains too personal for a business letter, while using a family name alone without a title is disrespectful. Also, the gender-inclusive salutations “To Whom It May Concern,” “Dear Sir or Madam,” or “Dear Author,” sound distant and impersonal.

In this changing environment, editorial boards may wish to weigh political correctness against traditional formality when deciding on a standard for their salutation line.

Closing salutations

There are a number of closing salutations in English, which vary in tone and formality (Fig. 1). In general, “Sincerely,” is by far the most appropriate closing salutation for a business letter, whether writing to a stranger or to an acquaintance. Be wary of the friendly series of “Best” salutations, such as “Best regards,” or “Best wishes,” as these are not generally used in a business letter unless the signatory is on familiar terms with the addressee. Using “Best,” alone is somewhat trendy and informal and should be avoided except when writing to friends.

Tips for Writing Formal Letters

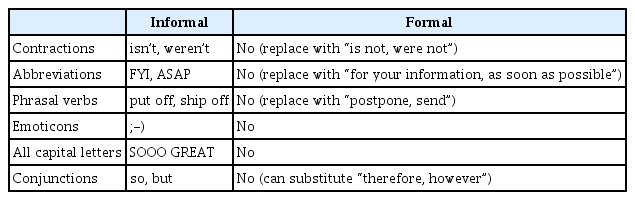

Avoid contractions

Contractions (such as “I’d,” “you’re,” “it’s,” “won’t,” and so on) are representations of the spoken language and should not be utilized in formal written English. Instead, write out the words in full to maintain formality.

Avoid abbreviations

Abbreviations (such as the acronyms AIDS and NASA and the initialisms FYI and ASAP) are frequently employed in English to reduce the length of commonly used expressions. In general, it is best to avoid abbreviations in formal writing if possible. For example, FYI, meaning “for your information” and ASAP, meaning “as soon as possible” should be written out; however, acronyms that are well-established words (such as laser, which derives from “light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation”) may be used without explanation, as may abbreviations that all readers in a given field would be expected to be familiar with (as with the above-mentioned example of “AIDS”). If necessary, less familiar abbreviations may be utilized after first being introduced in full, followed by the abbreviation in parentheses, like in “Science Editing (SE).”

Replace phrasal verbs

Phrasal verbs are verb phrases composed of two or three parts, such as a verb plus preposition, that take on a different meaning than when the verb itself is used alone. For instance, the verb “put” means “to place,” but the phrasal verb “put off” means “to postpone.” Phrasal verbs, especially expressions with “get,” should be avoided where possible in formal writing (Table 1).

Use formal word choice

Word choice can also make writing sound more formal. For instance, single-syllable commonly used words, such as “good,” are considered more informal than their multisyllabic counterparts, such as “beneficial.” To employ more sophisticated language, refer to a thesaurus (https://www.thesaurus.com/) or the Academic Word List [11].

Use polite expressions and sentence frames

Some NNES writers may be unaware of the connotations (evoked feelings) or lack of politeness attached to certain English words since the same words in their native language may not be offensive. For instance, when making requests in English, the word “want” should be avoided. Though the meaning is clear, the word “want” is generally considered direct, demanding, or even childish, depending on the context. Similarly, when making apologies, “I am (so) sorry” is relatively personal and may typically be found in spoken language. For a business letter, it is more appropriate to use a form of the word “apologize,” which sounds both formal and polite (Table 2).

Forestalling Unintentional Rudeness

Critiquing an individual’s work is a delicate matter, especially when writing in a second language where cultural differences may lead to unintentional offense. Here are some tips to help ease the delivery of corrections, criticisms, or outright rejection of submissions.

Customization, explication, and praise

Though it may be tempting to employ a letter template to reject a submission, Cortini et al. [9] have shown that customizing a rejection letter affects the perception of fairness and intention to re-apply. Editors may customize a letter by addressing the recipient formally using the author’s name and title (“Dear Professor Smith,” not “Dear Lisa,”); including the title of the submission; offering some lines of sincere praise for worthy aspects of the paper; and providing a gentle explanation as to why the manuscript is not suitable at this time.

Framing matters positively

Whether writing a letter of acceptance or rejection, acknowledging the research in a positive way should lead to the researcher’s improved self-concept [6], while providing negative feedback may negatively affect performance on a future task [7]. In rejection letters, the editor may wish to encourage the researcher to continue to improve the paper for future resubmission once it meets the journal’s standards. Rather than framing the rejection negatively (“Your submission does not meet our standards”), a positive approach with specific details may be more effective (“Your research on COVID-19 mutations is timely and would be of interest to our readers; we encourage you to resubmit your paper for consideration after expanding the methodology section and providing a more extensive discussion of the results”).

Using indirect language

With the intention of being polite, editors sometimes use indirect language. While academic correspondence should be clear, specific, and polite, it is necessary to find a balance between directness, which makes the point clear, and indirectness, which is more courteous but less clear. For example, when an editor writes, “The author might want to consider providing X for Y,” NNES authors may interpret this indirect comment as an optional suggestion and may not make any corrections. Instead, an editor could write (1) “I am not sure that I fully understand this claim” or (2) “In my opinion, Fig. 3 is an important example; however, I think XYZ are not well-summarized.” These non-confrontational indirect statements should trigger a revision without hurting anyone’s feelings.

In Western social convention, there is a tendency to be more indirect when giving criticism to a stranger than when giving criticism to a friend. However, excessive use of indirect language may feel circular, evasive, or tedious to some Westerners. Therefore, while indirect language may be a highly successful technique for avoiding offense, it should be used selectively and interspersed with other techniques to soften criticism in the editorial realm.

Hedging

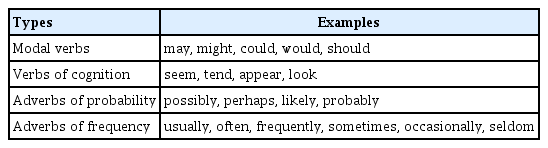

An alternative to the circularity of indirect language is to selectively employ hedging. Hedging incorporates the intentional use of indecisive expressions to minimize certainty or to depersonalize a message. Hedging is commonly used in academic research by native speakers [12,13] and can be extended to peer review as a way to provide socially acceptable criticism. There are several ways to hedge (Table 3).

Modal verbs: The modal verbs “may,” “might,” “could,” “would,” and “should” soften the expression of obligation in comparison to “must.” “You must replace the nouns with pronouns” is a command demanding full compliance. “You should replace the nouns with pronouns” is strong advice but is not fully obligatory. “You might replace the nouns with pronouns” suggests a possibility with little to no obligation.

Verbs of cognition: The “be” verb with a complement sounds very definite. Replacing it with a verb of cognition reduces the strength of the claim and, therefore, the offensiveness. “Your facts are incorrect” is a blunt statement expressing 100% certainty. “Your facts appear to be incorrect” allows a margin of error.

Adverbs of probability: Adverbs of probability can be employed to express the level of definiteness. “The discussion is too abstract” is a statement of 100% certainty. “The discussion is likely too abstract” leans toward certainty, but allows for a varying opinion. “The discussion is perhaps too abstract” introduces uncertainty of an unknown dimension.

Adverbs of frequency: Messages can also be moderated by selectively claiming that a condition does not exist 100% of the time. “The journal frequently accepts papers with fewer than 25 citations” is encouraging. “The journal occasionally accepts papers with fewer than 25 citations” softens discouragement.

Selective adjectives: Another way to hedge is with adjectives. When we compare (1) “The conclusion needs revision” with (2) “The conclusion needs minor revision,” sentence (1) sounds discouraging, while sentence (2) sounds encouraging.

Softening “you”: Sentence patterns beginning with “you” can feel demanding or accusatory. As an alternative, psychologists recommend we begin with “I statements” (such as “I think” or “I believe”) to let the other person know that we are speaking from our own perspective. When we compare (1) “You did not include enough data in your tables” with (2) “I feel that you did not include enough data in your tables,” sentence (1) sounds direct and accusatory, while sentence (2) shifts the blame slightly.

Impersonal clauses: To depersonalize the message, remove “I” and begin with a clause in the third person, such as in (1) “It may improve the paper to extend the methods section,” and (2) “The results indicate that further analysis is warranted.”

Conclusion

Editors need to be both polite and prudent when communicating with authors. Selecting an appropriate greeting and closing and using culturally acceptable statements and tone, particularly when writing rejection letters, can all be very difficult tasks for NNES editors. Becoming acquainted with the basic format and principles of writing formal letters and applying various strategies to mitigate criticism will help editors to communicate with authors with confidence and efficiency.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for this article.

References

Appendix

Appendix 1. Structuring a formal email